Author Interviews

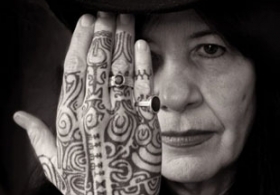

Writing The Story: My Interview With Joy Harjo

Guest Blogger: Jekeva Phillips

I have a confession to make: I happen to be an unfortunate member of the dead white guys book club. For eons—okay, well, not eons, but it has certainly been decades since the moment I picked up my first book—I have held the works of Hemingway and Kafka as sacrosanct. No storyteller could equal Fitzgerald, Updike, Faulkner, and Melville; their prose, seductive like the Erlking carrying me through the wonderfully white worlds of silk shirts and sea voyages.

But these are stories have been written by the “winners of history”, their words the dominant point of view, conquering the literary world just as they have history books. Story has the immense power to either help or heal, to beleaguer or to vindicate. It is a rallying cry, a voice that refuses to be silenced. In each and every one of us there is a need to tell our story, share our histories, our suffrages—to bare our roots.

There are few authors whose voice is able to shake the cannon of dead white guys. Joy Harjo happens to be one of them. Her triumph over alcoholic and abusive father figures, a dangerous flirtation with suicide, and the hardships of teen motherhood is chronicled in Crazy Brave. Joy’s debut memoir is a quest of the human spirit. Her prose is a sheer force of resilience, not only for herself, but for thousands of Native American women who have been beaten down. Like so many other authors, Joy has used her art to reel her back from the brink of destruction. “It was the spirit of poetry,” she writes in Crazy Brave, “who reached out and found me as I stood there at the doorway between panic and love.”

After months of trying to interview this elusive woman, I was lucky enough to catch her on a day where she was between book tours and traveling off to foreign lands with her band, Poetic Justice.

“To express yourself or to find yourself in any artistic expression is to give birth to new ideas,” Joy begins. “In culture and history, art has always served this purpose. We talk about art being self expression, but what is ‘the self’? There is so much history to ‘the self,’ it is connected to family, to country, and mythology.”

Crazy Brave is a book that was 15 years in the making. “Sometimes, it’s just not the right time, but try telling that to your editor,” she jokes as she lists the different versions the autobiography took on over the years, one of which included a series of vignettes each wrapped around a song. As she continues, I begin to think perhaps her editor was onto something. How long does it really take to write your own life? “Part of that 14 years was running away from the story,” she finally confesses. “I got about halfway through one version, and I realized I was still running away; that I was trying to distance myself from the story that was trying to be written.

“It took me 14 years because I carried a lot of shame, [shame] that I had been in a relationship with someone who beat me…”

The plight of Native Americans is unfortunately a well-kept secret across the nation, especially when it comes to women. Although there has been some light shed on the matter, the most recent being Native writer Louise Erdrich’s take on governmental strides of the Violence Against Women Act, the reality is far too disturbing to bare. According to U.S. Department of Justice, Native Americans account for 1.2% of the population, yet 1 in 2 Native women will be raped in her lifetime. In some areas, Native women are 10 times more likely to be murdered than the national average. 1

To make matters worse, reservation authorities and care providers are far too understaffed and underfunded to help their victims. These injustices are rarely brought to light because, let’s face it: in news, media, and even in entertainment, Natives are an afterthought.

There are few representations of Natives in America. What we learn in school is minuscule comparable to their actual history. Natives have been so effaced in society that even Natives cannot point to one contemporary icon. “I’m trying to think…. [of anything] in popular culture that really shows our people,” Joy says, trying to fill the pause that has suddenly fallen over our conversation. “Osceola,” She mentions “or the Trail of Tears photos, but those only give people a vague sense of travesty and injustice.” A polite ‘hmm’ is all I add to the conversation; I had never heard of Osceola, and the trial of tears photos are a distant memory. I do, however, recall in vivid detail the Indians of the wild west; the painted faces of the actors in The Paradise Syndrome —begrudgingly one of my favorite episodes of the original Star Trek. Joy has attempted to break the mold by trying to bring accurate representations of Natives to Americans, but as she has come to discover, “If we are not dancing, making war, or acting sappily spiritual, then we don’t exist. We’ve been pretty much disappeared in [American] culture.”

The Native point of view, women in particular, have had their voices stolen from them, and, as Joy Harjo has often said, it has forced women to turn their anger inward. “I think we do it because we have to save our lives. Sometimes we do it because as women, we have to negotiate. At times, I have felt that there was too much anger and that when I let it out, it was very destructive… it only gives back more anger.”

Author of seven poetry books, an award-winning children’s book writer, and international musician; Joy is a perfect specimen of how the power of story can change a life. Joy’s journey of finding strength through prose, is a method sought out with an unconscious fervor. Acclaimed author Steve Almond writes about himself as a young man in his twenties, “I was living in exile from my family and driving away the people I loved with an astonishing efficiency. What I needed was therapy. As it happened, I applied for a Master of Fine Arts in fiction.” 3 Writing has been used in countless forms of therapy across a multitude of ages, including children. 4

“When I write, I always learn things that I don’t know,“ Joy tells me. “I’m familiar with what I’ve been through, but the art of it helped me to understand and comprehend it in ways that I wouldn’t have written otherwise. … I came to realize that I was a story and you can use the story to destroy you: ‘I must have done something to deserve this,’ or ‘everybody hates me,’ or ‘I don’t fit in.’ …It’s all in how you tell the story to yourself. I was hurting myself by contributing to a story that would box me in.

“About a year before I got Crazy Brave published, I finally sat down and I said, ‘I give up.’ Then my writing self started taking over… and that is what Crazy Brave is about, being brave enough to say ‘yea, I went through that.’”

It would seem that a very old cliché is quite fitting for this occasion: the pen is indeed mightier than the sword. With it, we have the power to discover the truth inside of us, to seek out what ails us and snuff out the anger with each stroke of ink, to write what has previously been effaced. It is an integral part of understanding, or as Joy has taught us, writing the story out so it does not hurt you anymore.

About the Author

Jekeva is the editorial Coordinator for AllTreatment.com. She is a huge lover of literature, and an advocate of drug and alcohol awareness. She sees it as her mission to ensure that people in the throes of addiction get the help they deserve.